RESOURCES

Guidelines

- BTS (2010) – Pleural procedures and thoracic ultrasound

- BTS (2003) – Guidelines for the insertion of a chest drain

Documents

Review Articles

OBJECTIVES & QUESTIONS

Overview

What are the indications for a chest drain?

-

- Pneumothorax:

- In any ventilated patient

- Tension pneumothorax after initial needle

relief - Persistent or recurrent pneumothorax

after simple aspiration - Large secondary spontaneous pneumothorax

- Malignant pleural effusion

- Empyema and complicated parapneumonic

pleural effusion - Traumatic haemo-pneumothorax

- Postoperative (for example, thoracotomy, oesophagectomy, cardiac surgery)

- Pneumothorax:

Insertion Considerations

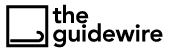

Where should a drain be placed anatomically?

- Usually placed in the ‘Triangle of Safety’:

- Anterior border of latissimus dorsi

- The lateral border of the pectoralis major

- A line superior to the horizontal level of the nipple (5th intercostal space)

- Apex below the axilla

- It is a safe place because of its location above the diaphragm and a very thin chest wall musculature, allowing rapid and minimally painful insertion

- A more posterior position may be chosen in the presence of a locule but while this is safe:

- Must be inserted under imaging

- Not the preferred site as it is more uncomfortable for the patient to lie on after insertion, and there is a risk of the drain kinking

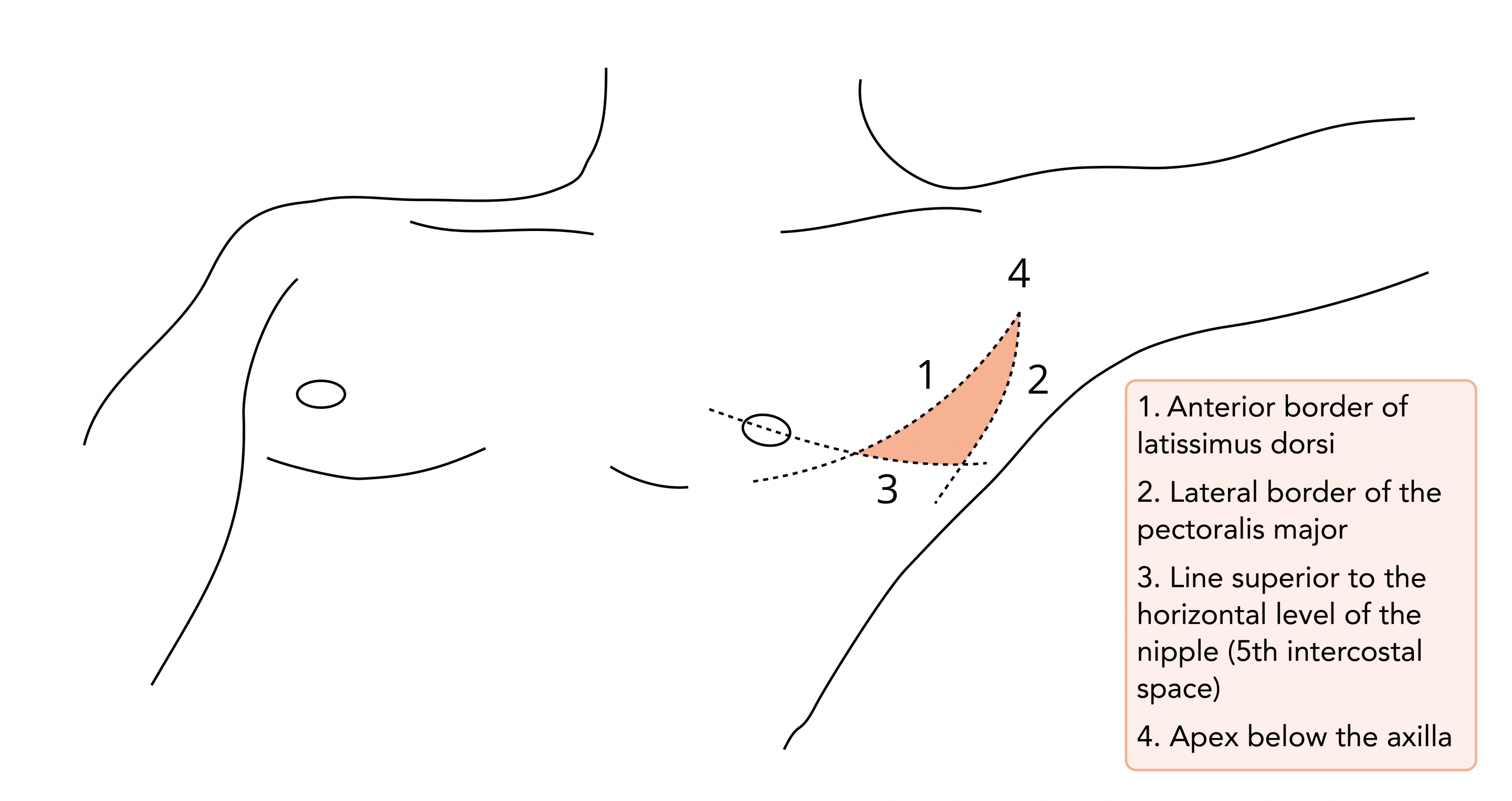

Where should a drain be placed in relation to the ribs?

- The intercostal spaces are filled with:

- Intercostal muscles,

- Intercostal vein, artery, and nerve – lying in the costal groove along the inferior margin of the superior rib

- To avoid the neurovascular bundle, it is typically advocated that the drain be located in the interspace just superior to the rib

Where should the tip of the chest drain lie?

- Position of the tip should depend on the indication for insertion:

- Aim apically for a pneumothorax

- Aim basally for fluid

- However, any tube position can be effective at draining air or fluid – tubes should not be repositioned solely based on the radiographic position

How should you secure a chest drain?

Sutures

- Two sutures should be used

- One stay suture to assist with later closure

- Sutures to secure the drain – usually suture across a linear incision

- Purse string sutures should not be used – leave unsightly scars and can be painful

- Sutures should be strong and non-absorbable (usually “1” silk)

- Usually not required for small drains

Dressings

- Avoid large amounts of tape and padding

- Transparent dressing to allow inspection for leakage and infection

- And omental tag of tape allows movement and avoids kinking

When should ultrasound be used?

- Strongly recommended for all pleural procedures for pleural fluid

- Particularly useful for defining the diaphragm and pleural thickening in:

- Loculated effusions

- Empyema

- The marking of a site by ultrasound for subsequent remote aspiration (by a radiologist) is strongly discouraged

What are the advantages of using ultrasound?

- Lower failure rate

- Reduced risk of complications – particularly:

- Pneumothorax

- Visceral organ perforation

When should chest drains be performed?

- Chest drain insertion should not be performed out of hours unless an emergency

- Significant respiratory compromise

- Significant cardiovascular compromise

- Recommendation is due to research suggesting higher complications of surgical procedures out of hours

Do you need to give the patient antibiotics before placing a chest tube?

- There is considerable debate about the use of prophylactic antibiotics following chest drain insertion

- BTS guidance suggests:

- Prophylactic antibiotics should be given in the case of insertion for trauma

- There is no evidence for there use in other circumstances

- Generally when used a single dose of antibiotics with good gram-positive coverage is used

Complications

What are the complications of chest drains?

Insertion Related

- Intercostal vessel laceration and haemothorax

- Lung parenchyma perforation

- Perforation of visceral organs (lung, heart, oesophagus, diaphragm, and intraabdominal organs)

- Interfissural - usually does not affect outcome

- Chest wall insertion - unstable chest wall injuries, hurried insertion

- Chylothorax - late complication due to injury to thoracic duct

Position Related

- Drain dislodgment - can be reduced by meticulous technique and good anchorage

- Non-functional (Kinked, clotted) - can result in tension pneumothorax

- Subcutaneous emphysema - associated with prolonged drainage, poor tube placement and side port migration

- Post-removal pneumothorax - can be reduced by good removal technique

Infective

- Empyema

- Insertion site wound infection

Nerve Injury

- Intercostal neuralgia

- Phrenic nerve injury

- Horner's Syndrome

Other

- Re-expansion Pulmonary Edema - uncommon but mortality up to 20%

What is re-expansion pulmonary oedema?

- An uncommon but sometimes fatal complication of pleural drainage:

- One historical case series reported mortality as high as 20%

- Usually presents on the side of the lung re-expansion (though contra-lateral and bilateral cases have been reported)

- Clinical features are wide-ranging:

- Maybe asymptomatic

- Cough, discomfort and nausea

- Dyspnoea, pink frothy sputum and hypoxia

- Fever, tachycardia and hypotension

- Radiological features are of pulmonary oedema and interstitial opacities

- Aetiology is unclear but likely includes altered capillary permeability and loss of protein-rich exudate

What are the risk factors for re-expansion pulmonary oedema?

- Young age (<40 years)

- Lung collapse for >3 days

- Large pneumothorax (>30% of the single lung)

- Application of negative pressure suction

- Rapid lung re-expansion

How can you prevent and limit re-expansion pulmonary oedema?

- Recognize those at high risk

- Limiting the rate of fluid drainage:

- No more than 500ml per hour

- Clamp tube for 1 hour after draining 1 litre

- Drain no more than 1.5 litres at any time

- Leaving drains of suction initially

How do you treat re-expansion pulmonary oedema?

- Usually supportive care as condition is often self-limiting

- Oxygen and invasive ventilation may be necessary

- If unilateral oedema positioning with the affected side up can reduce shunting and improve oxygenation

Chest Drains

What types of chest drain are available?

Small Bore Tubes

8-14 Fr

- Usually inserted via Seldinger

- Do not require blunt dissection

- Better tolerated by patients

- Provide better seal

- Have been successfully used for pneumothorax, effusions or empyema

- Narrow lumen prone to blockage

Medium Bore Tubes

16-24 Fr

- Inserted by a Seldinger technique or blunt dissection

- Not possible to insert a finger to explore when inserting these tubes

Large Bore Tubes

>24 Fr

- Blunt dissection must be performed requiring basic surgical kit

- Finger sweep at insertion avoids lung trauma

- Less prone to blockages

- More painful insertion and whilst in situ

Which chest drain should be used?

- No evidence that either small or large bore drains therapeutically superior

- Small-bore drains are recommended as they are more comfortable than larger bore tubes

- Remains intense debate about the optimum size of drainage catheter

Pneumothorax

- Small bore drains usually recommended

- Medium bore drains should be considered for pneumothorax with mechanical ventilation

- Large bore drains should be considered for traumatic pneumothorax where blood may be present in addition to air

- Large bore drains recommended when a drain has failed to resolve a pneumothorax due to excessive air leakage

Pleural effusion (Malignant, parapneumonic or empyema)

- Small bore drains usually recommended

- Medium bore drains should be considered for more viscous fluid

Haemothorax

- Large bore drains recommended for drainage of haemothorax and assessment of ongoing haemorrhage

Drainage Bottles

What is the purpose of a chest drain bottle?

- Allow air and fluid to leave the chest – achieved by gravity drainage

- Prevent air and fluid from returning – achieved through the use of a one-way valve

- Restore negative pressure in the pleural space to re-expand the lung – achieved through the use of an air-tight system

What types of drainage systems are available?

- Flutter (Heimlich) valve

- Closed underwater seal bottle:

- One chamber system

- Two-chamber system

- Three chamber system

- Digital drainage system

How does a one chamber underwater seal system work?

- The underwater seal created by a tube placed 2-3 cm below the surface of the water:

- Ensures minimum resistance to drainage of air and fluid

- Acts as a one-way valve preventing re-entry during inspiration

- The chamber should be 100 cm below the chest

- During expiration:

- Fluid or air drain into collection chamber under gravity

- Bubbles are seen in the case of pneumothorax

- During inspiration:

- Negative pressure is generated in the pleura

- Creates retrograde flow of fluid up the tubing (respiratory swing)

- Low height of chamber and length of tubing prevents fluid reaching the pleural cavity

- Respiratory swing useful for assessing tube patency and pleural position

How does a three chamber underwater seal system work?

Bottle 1

- No water prime and acts purely as a collection reservoir for fluid

- Air from the pleural cavity passes into the second bottle

Bottle 2

- Has an underwater seal with tubing tip 2-3cm below the water

- Acts as a one way valve as in a classic one chamber system

Bottle 3

(Not Always Required)

(Not Always Required)

- Exists to provide and control negative pressure suction to the system

- 3 tubes attach to the top:

- First connects to bottle 2

- Second connects to the suction pump

- Third connects to the atmosphere and water prime, and controls the magnitude of suction

- Suction is applied to the bottle making the pressure more negative and entraining air from the second bottle

- The degree of suction is controlled by the depth of the 3rd tube in the water prime. If it is set to 10cm below the water, no more than - 10cm H2O of pressure can be applied to the bottle as below this air will be entrained from the atmosphere and will be seen bubbling through the water prime

What should the features of the drain tubing be?

Length

- Long enough to keep 80–100 cm below the patient to prevent water being entrained during inspiration

- Negative pressures of 50–80cm H2O can be generated in some people.

Volume

- At least 50% of the patients vital capacity to help prevent water being drawn back from the bottle

Management of Drains in Situ

How can you avoid drains becoming blocked?

- Observe drain tubing for debris or clots

- If blockage suspected flush with saline

- For small drains, consider flushing 6–12 hourly with 5–10ml of 0.9% saline to assess and maintain patency

Should a chest drain ever be clamped?

- A chest drain that is bubbling should never be clamped – the risk of tension pneumothorax

- There are a few reasons why drains may be clamped:

- During the drainage of extensive fluid, collections to prevent re-expansion pulmonary oedema

- Under specialist instructions to assess for air leaks

- No evidence clamping a chest tube before assess removal is beneficial and is generally discouraged (BTS)

- However, many physicians support the use to detect small air leaks not immediately obvious at the bedside

- A drain may be clamped for several hours, followed by a chest radiograph to assess for increased pneumothorax

- If performed must be on a ward with nursing staff trained in the management of chest drains

- If a patient with a clamped chest drain becomes breathless or deteriorates clinically the clamp should be released immediately

What is the role of suction with chest drains?

- Suction is generally not required and should not be used routinely

- Maybe advocated:

- In cases of non-resolving pneumothorax

- Following chemical pleurodesis

- If used should be a high volume/low-pressure system

- Can be achieved through the use of:

- An underwater seal at a level of 10–20 cm H2O

- A high volume pump (e.g. Vernon-Thompson)

When should you remove a chest drain?

In general, a chest drain can be removed when:

- The patient’s clinical condition has improved

- The lung has fully re-expanded on chest imaging

- There is no air leak (bubbling in the drain) on Valsalva manoeuvre or cough

- There is minimal fluid drainage:

- Exact amount depends upon the indication

- Generally <100-150ml / day

- Any fluid drained is serous

How should a chest drain be removed?

- Should be removed with the patient either:

- Performing a Valsalva’s manoeuvre

- During expiration

- A brisk firm movement should be used

- An assistant should be present to tie the previously placed closure suture

- An X-ray should be performed and reviewed post-removal to assess for pneumothorax

Troubleshooting

What issues can arise with chest drains and how can you deal with them?

Cause

Outcome

Action

Drain not bubbling or swinging

The absence of a swing may indicate that the tube is blocked.

- If the drainage in the tube is impeded, there is potential risk for a tension pneumothorax or surgical emphysema to occur

- Assess the patient

- Check for kinks in the tubing

- If a clot is seen in the tubing, gently squeeze or pinch the tubing between the fingers in the direction of the drainage device. If there is no improvement change the tubing

- Get senior help

Lack of drainage

The lack of drainage may indicate that the drain is blocked or kinked

- Tension pneumothorax

- Assess the patient

- Check the entire system for kinks and obstructions

- Straighten the tube

- If unresolved get senior help

Tube becomes disconnected

Connections not adequately secured

- Air will enter the pleural space casing a worsening pneumothorax and/or tension pneumothorax

- Clamp tubing to prevent air entering the pleural space

- Ask another member of staff to assess the patient

- Replace with new tubing

- Ask the patient to cough gently to remove air

- Get senior help

Leakage from drain site

- Incomplete closure of sutures

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Surgical emphysema, sepsis and empyema

- Remove dressing, check wound and send swab

- Check integrity of sutures

- Assess the patient

- Inform medical team and consider blood cultures and antibiotics

Continuous bubbling

- Leak from chest drain connections

- Persistent air leak within the lung

- Unresolved pneumothorax

- Assess the patient

- Check drain, connections and tubing

- Get senior help

Sudden increased blood or fluid losses in drain

- Drain previously blocked

- Thoracic bleeding

- Hypovolaemic shock

- Immediately get senior help

- Assess the patient

- >1500ml loss of blood or 200ml/hour may indicate the need for a thoracotomy

Tube eyelets are exposed

Chest drain has moved

- Air will enter the pleural space casing a worsening pneumothorax and/or tension pneumothorax

- Get senior help

- Cover the tubing with an occlusive dressing

- Assess patient

Chest drain falls out

Drain not secured

- Respiratory distress due to pneumothorax

- Get senior help

- If mattress suture present close the wound and apply an occlusive dressing

- Assess patient

- Prepare for a chest drain insertion

Pain

- Drain pulling at site

- Immobility

- Pneumothorax

- Hospital acquired pneumonia

- Stiff shoulder

- Respiratory distress

- Assess patient

- Review and adjust analgesia

- Refer patient to the physiotherapist

Procedure

How do you insert a surgical chest drain?

- Sterile gloves and gown

- 2% chlorhexidine cleaning fluid

- Sterile drapes

- Gauze swabs

- Local anaesthetic, syringe and needle

- Scalpel and blade

- Suture (e.g. “1” silk)

- Appropriate dressing

- Underwater seal drainage bottle and tubing

- 3-way tap (optional)

- Sterile Water

- Scalpel

- Blunt dissection forceps (e.g. curved Robert’s)

- ICS / FFICM or Local Safety Checklist

Key Considerations:

- Risk Assessment

- Consent

- Premedication

- Imaging

- Positioning

Risk Assessment

- Assess and correct coagulopathy

- Assess appropriateness of drain insertion:

- Can be difficult to tell between:

- Large bulla and pneumothorax – seek expert advice

- Collapse and effusion in unilateral “white-out”.

- Should not be performed when lung densely adherent to wall throughout hemithorax

Consent

- Explain the risks of the procedure and complete a consent form

- Complete a consent form 4 for ventilated patients

Premedication

- Often reported as a very painful procedure:

- Examples from BTS guidance – no clear superior choice

- Intravenous anxiolytic—for example, midazolam 1–5 mg titrated to effect

- Intramuscular opioid given 1 hour before

Patient Positioning

- Preferred – On the bed, slightly rotated, with the arm on the side of the lesion behind the patient’s head to expose the axillary area

- Alternative – Patient to sit upright leaning over an adjacent table with a pillow or in the lateral decubitus position.

- Complete safety checklist

- Ensure full sterile clothing worn

- Clean the area of drain insertion with chlorhexidine – the so-called ‘safe triangle’ – and drape with sterile towels

- Palpate the anatomy and identify the optimal site for drain insertion

- Infiltrate local anaesthetic to the skin and subcutaneous tissues at the point of insertion, taking care to avoid the neurovascular bundle at the inferior border of the rib.

- Free air or fluid should be aspirated using your needle at the time of local anaesthetic infiltration – if not stop and seek expert advice for real-time imaging (BTS Guidance)

- Make a 2–3cm incision along the upper edge of the rib that makes the inferior border of the relevant rib space

- Using forceps, bluntly dissect into the pleural cavity

- Perform a finger sweep of the pleural cavity – enhances blunt dissection, breaking down loculations and acts as a diagnostic examination

- Hold the tip of the drain with the forceps by the distal side hole

- Gently insert the drain into the pleura, aiming either apically or basally as desired with the forceps, and release. Disconnect the patient from mechanical ventilation at the point of insertion to reduce the risk of intrapulmonary placement

- Connect to an underwater sealed drainage bottle

- If required for sampling attach a 3-way tap to the system for sampling

Securing the Drain

- Suture one end of the incision and place an anchoring suture around the drain

- Pad and stick to the skin using a small transparent dressing. Consider a tape mesentery to prevent kinking

- If used ensure the 3-way tap is accessible

- Document the procedure in the patient’s notes

- Request and review a chest x-ray to check the position of the drain

- Record plan for fluid drainage if effusion:

- No more than 500ml in 1st hour

- No more than 1500ml in 24 hours

Procedure

How do you insert a Seldinger chest drain?

- Sterile gloves and gown

- 2% chlorhexidine cleaning fluid

- Sterile drapes

- Gauze swabs

- Local anaesthetic, syringe and needle

- Scalpel and blade

- Suture (e.g. “1” silk)

- Appropriate dressing

- Underwater seal drainage bottle and tubing

- Sterile Water

- Bedside ultrasound

- Seldinger insertion kit:

- Needle and syringe

- Guidewire

- Scalpel

- Dilator

- Drain with stiffener

- 3-way tap

- ICS / FFICM or Local Safety Checklist

Key Considerations:

- Risk Assessment

- Consent

- Premedication

- Imaging

- Positioning

Risk Assessment

- Assess and correct coagulopathy

- Assess appropriateness of drain insertion:

- Can be difficult to tell between:

- Large bulla and pneumothorax – seek expert advice

- Collapse and effusion in unilateral “white-out”.

- Should not be performed when lung densely adherent to wall throughout hemithorax

Consent

- Explain the risks of the procedure and complete a consent form

- Complete a consent form 4 for ventilated patients

Premedication

- Often reported as a very painful procedure:

- Examples from BTS guidance – no clear superior choice

- Intravenous anxiolytic—for example, midazolam 1–5 mg titrated to effect

- Intramuscular opioid given 1 hour before

Patient Positioning

- Preferred – On the bed, slightly rotated, with the arm on the side of the lesion behind the patient’s head to expose the axillary area

- Alternative – Patient to sit upright leaning over an adjacent table with a pillow or in the lateral decubitus position.

- Complete safety checklist

- Ensure full sterile clothing worn

- Clean the area of drain insertion with chlorhexidine – the so-called ‘safe triangle’ – and drape with sterile towels

- If being performed for fluid real-time ultrasound should be performed throughout the procedure to guide site of infiltration and drain insertion

- Infiltrate a small volume of lidocaine into the skin and subcutaneous tissue

- Free air or fluid should be aspirated using your needle at the time of local anaesthetic infiltration – if not stop and seek expert advice or real-time imaging (BTS Guidance)

- Insert the introducer needle, whilst aspirating using a syringe, until air/ fluid is freely withdrawn

- Having entered the pleural space, disconnect the syringe and gently insert the guide-wire through the needle

- Withdraw the needle, leaving the wire in situ

- Make a small stabbing incision through the skin at the exit site of the wire. This is most easily performed by placing the flat surface of a no. 11 blade on the wire and sliding it into the skin

- Insert the dilator into the pleural cavity over the wire; be cautious not to insert this too far and angle the tract formed towards the desired location:

- Apical for simple pneumothorax

- Posterior-basal for fluid

- Leave the dilator in place for a few moments, then remove, again leaving the wire in situ

- Ensure drain mounted over stiffener and gently insert, over the wire

- Chest drain insertion should be performed without substantial force

- Disconnect the patient from mechanical ventilation at the point of insertion to reduce the risk of intrapulmonary placement

- Withdraw the wire and stiffener then connect to a closed 3-way tap

- Aspirate via the tap to ensure adequate placement and anchor with a holding suture

- Connect to an underwater sealed drainage bottle

- If required for sampling attach a 3-way tap to the system for sampling

Securing the Drain:

- Suture one end of the incision and place an anchoring suture around the drain

- Pad and stick to the skin using a small transparent dressing

- Consider a tape mesentery to prevent kinking

- If used ensure the 3-way tap is accessible

- Document the procedure in the patient’s notes

- Request and review a chest x-ray to check the position of the drain

- Record plan for fluid drainage if effusion:

- No more than 500ml in 1st hour

- No more than 1500ml in 24 hours

- Consider prescribing routine saline flushes for small caliber drains to prevent blockages