RESOURCES

Guidelines

Review Articles

- Astigarraga et al, An Pediatr (2018); Haemophagocytic syndromes: the importance of early diagnosis and treatment

- Schram et al, Blood (2015); How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the adult patient

- Brisse et al, Cytokine & Growth Reviews (2014); Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): A heterogeneous spectrum of cytokine-driven immune disorders

- George, J Blood Med (2014); Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: review of etiologies and management

Usmani et al, BJH (2013); Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of HLH

OBJECTIVES & QUESTIONS

Introduction

What is hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)?

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an aggressive and life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome, which requires prompt and aggressive treatment

- It is termed macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) when associated with rheumatic disease and secondary HLH (sHLH) when associated with other triggers, including malignancy and infection

- HLH represents a group of conditions with different pathogenetic roots but a shared common final pathway

- It most frequently affects infants up to 18 months of age but can be seen in children and adults of all ages

What is haemophagocytosis?

- Defined by the presence of intact hematopoietic cells (erythrocytes or leukocytes) within the cytoplasm of phagocytic macrophages (histiocytes) in any tissue

- The identification of hemophagocytic histiocytes in bone marrow is a fundamental diagnostic feature of HLH:

- However, the diagnosis can be made even without the presence of haemophagocytosis in biopsied tissue (non-sensitive)

- Other causes can lead to the presence of haemophagocytosis, including prolonged sepsis, infection (viral, fungal, parasitic) and malignancy

Why is HLH relevant to intensive care?

- Usually requires ICU management given the severity of clinical features

- Often first diagnosed in patients with known sepsis or multi-organ failure:

- Has non-specific symptoms and laboratory findings

- Requires ICU clinicians to have a high index of suspicion

- Has specific treatments available but a poor prognosis without

Epidemiology, Clinical Course & Prognosis

How common is HLH?

- Estimated at <1 per 100,000 children under 18

- Likely to be significantly under-recognised

- Incidence may be as high as 1 in 2000 adult admissions at tertiary medical centres

Which age groups is HLH seen in?

- Traditionally considered a disease of children, particularly those <18 months

- Adults now comprise up to 40% of cases of HLH:

- Median age of diagnosis being mid-40s to 50s

- Cases are even seen above age 70

What is the prognosis of HLH?

- Primary HLH is almost universally fatal without treatment

- Mortality improved with treatment

- Approximately 50% with HLH-94 based treatment

- Secondary HLH and HLH in adults without treatment has high mortality:

- Overall mortality of 50% to 75%

- Stem cell transplant has resulted in significant improvements in long term survival and cure

What are the poor prognostic factors?

- Younger age

- CNS involvement

- Failure of therapy to induce a remission before HCT

- Association with malignancy

Aetiology

What are the causes of HLH?

Primary

Primary

- Genetic defects – usually autosomal recessive:

- Function of cytotoxic T cells or NK cells

- Inflammasome regulation

Secondary (Acquired)

Secondary (Acquired)

- EBV

- HSV

- HIV

- CMV

- Bacterial

- Protozoal (Malaria, Leishmania)

- Fungal (Candida, Aspergillus)

- Mycobacteria

- Mycoplasma

- Natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas

- B-cell lymphomas

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Leukaemia

- Other hematologic neoplasms

- Solid tumours

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- SLE

- Adult-onset Still's Disease

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Stem or bone marrow transplant

- Solid-organ transplant

- Severe combined / common variable immunodeficiency

- Haemodialysis

- Pregnancy

- Vaccination

Pathophysiology

What are the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms in HLH?

- Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes (CTLs) and Natural Killer (NK) cells eliminate infected or tumour cells via apoptosis

- When the cells are cleared, the CTLs will inhibit further antigen presentation by removing antigen‐presenting Dendritic Cells (DCs)

- T-Regulatory Cells (Tregs) compete with and limit the proliferation of CTLs. They may also directly eliminate activated CTLs

- NK cells likewise control the size of the activated CTL pool via induction of apoptosis

- This limits the amount of CTL‐derived IFN‐γ. This is required for macrophage activation and additional cytokine production, and so this becomes limited.

In the setting of HLH:

- Dysregulated immune system unable to restrict the stimulatory effect of various triggers (due to single or combined defects):

- CTLs and NK cells fail to eliminate tumour cells or infected cells, which continue to replicate, resulting in persistent antigenemia

- CTLs no longer remove the antigen-presenting DCs, leading to prolonged and heightened antigen presentation

- T Regulatory Cells are unable to regulate CTLs due to imbalanced cytokines. T regulatory cell numbers drop, and CTLs continue to proliferate.

- NK fail to control the size of the activated CTL pool due to loss of cytotoxic activity

- The activated CTLs produce massive amounts of IFN‐γ:

- Induces excessive macrophage activation

- Directly provokes haem phagocytosis.

- Activated macrophages release vast amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines (a ‘cytokine storm’):

- Interleukins: (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-16, IL-18

- Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)

- Results in ongoing cycles of inflammation and cytokine release:

- Exacerbated by failure to clear cells via apoptosis resulting in necrosis and further inflammation

How does the cytokine storm lead to the clinical syndrome?

- Fever

- Cachexia

- Depression of haematopoesis

- Hypertriglyceridaemia

- Elevated serum transaminases

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Suppression of NK cell activity

- Fever

- Haemophagoctytocis

- Depression of haematopoeisis

- Macrophage activation

- Stimulation of antigen presentation

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Fever Hyperferritinaemia

- Depression of haematopoeisis

- Acute phase proteins

- T-cell activation

- Fever

- Anaemia

- Acute phase proteins

- Renal failure

- Suppression of T-cell activation

- Regulation of haemophagocytosis

- Hepatic damage

- Supression of NK cell activity

Presentation

What are the typical clinical features of HLH?

Febrile illness (prolonged) associated with multiple organ involvement:

- Reticuloendothelial manifestations:

- Hepatosplenomegaly (95%)

- Lymphadenopathy (33%)

- CNS dysfunction (35%):

- Seizures

- Cranial nerve palsy

- Altered sensorium

- Respiratory dysfunction:

- Respiratory failure

- Alveolar / interstitial infiltrates

- Cutaneous manifestations (up to 65%)

- Maculopapular erythematous rashes

- Generalised erythroderma

- Oedema

- Panniculitis

What are the features of severe disease?

- High serum ferritin (>500, usually higher)

- Haematological abnormalities:

- Thrombocytopenia

- Anaemia

- Coagulopathy

- Hypofibrinogenemia

- Deranged LFTs:

- Hyperbilirubinaemia

- Transaminitis

- Hypertriglyceridemia

When should you suspect HLH in the ICU?

- Diagnosis can be challenging to make:

- Features are non-specific

- Physiological macrophage activation occurs in sepsis, malignancy and autoinflammatory disorders

- HLH is characterised by pathological macrophage activation

- Consider HLH in any critically ill patient with an inadequate response to treatment or unusual progression of symptoms:

- Persistent fever

- Unresponsive to vasopressors

- Inexplicable cytopenias

- Organ failure not responding to appropriate therapy and aggressive supportive care

Work-Up Summary

How do you work-up the patient with suspected HLH?

- Clinical history and findings

- Use of Clinical Scores:

- HLH Diagnostic Criteria (primary HLH)

- H-Score (secondary HLH)

- Laboratory evaluation:

- FBC

- Ferritin

- Fasting triglycerides

- Coagulation screen (fibrinogen, PT, aPTT)

- LFTs, LDH, albumin

- Immunological testing

- Bone marrow biopsy

If suspected, do not wait to treat!

- ADAMTS13 activity

- Anti-ADAMTS13 Ab

- Sequencing of ADAMTS13 gene

- Infection work-up:

- Relevant imaging

- Bacterial and viral studies

- Cancer work-up:

- PET-CT

- Tissue biopsy

- Tumour markers

Diagnostic Criteria & Scoring

How can HLH be diagnosed?

- Should be diagnosed based upon clinical judgement and history in conjunction with a diagnostic score/criterion

- Scoring systems available include:

- Produced in 2004 by the histiocyte society

- Developed for diagnosis of primary HLH in paediatric population

- Frequently applied to adult population though poorly validated

- Weighted criteria developed in 2014

- Only validated for secondary forms of HLH in adults

What are the diagnostic criteria for HLH?

The 2004 revision of the diagnostic criteria for HLH requires:

- Molecular testing consistent with HLH

or - 5 of 8 clinical or laboratory criteria

- Fever

- Splenomegaly

- Cytopenias of at least 2 cell lines

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Hypofibrinogenemia

- Elevated ferritin

- Elevated soluble IL-2 receptor (sCD25)

- Decreased or absent NK-cell activity

- Demonstration of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes

- Elevated transaminases

- Elevated bilirubin

- Elevated LDH

- CSF pleocytosis and/or elevated protein

What is the H-score?

- A set of weighted criteria, producing a score out of 337

- Score ≥169 commonly used as a cut-off as a likelihood for a diagnosis of HLH

- Produces a % risk of HLH based upon weighted score

Parameter

(Criteria for scoring)

(HIV or Immunosuppressive therapy)

18 (yes)

33 (38.4-39.4)

49 (>39.4)

23 (hepatomegaly or splenomegaly)

38 (hepatomegaly and splenomegaly)

(Hb <9.2 g/L / WBC ≤5 x 109/L / plat ≤110 x 109/L)

24 (two lineages)

34 (three lineages)

44 (1.5-4)

64 (>4)

35 (2000-6000)

50 (>6000)

Laboratory Investigations

What are levels of ferritin seen in HLH?

- The Texas children’s study (Allen et al) suggested:

- >500 has 100% sensitivity

- >10,000 has 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity

-

What is the role of ferritin in HLH?

- Believe that the very high ferritin levels are not just the product of the inflammation but instead may have a pathogenic role

- May be involved in some sort of a loop mechanism where ferritin’s inflammatory proprieties are exacerbated, leading to an extreme expression of additional inflammatory mediators that are characteristic in the cytokine storm.

Management Summary

How do you manage the patient with HLH?

Key Principles

- Provision of supportive care for organ failure

- MDT approach towards management

- Treatment of underlying cause

- Specific management based on HLH-94 protocol

- Aggressive approach to organ support - may require:

- Invasive ventilation

- Vasopressor support

- Renal replacement therapy

- Treat the underlying cause:

- Rheumatological - corticosteroids

- Infectious - antimicrobials

- For primary / refractory secondary disease HLH therapy based on the HLH-94 protocol:

- Etoposide

- Dexamethasone

- Intrathecal methotrexate

- If failure to respond additional treatments may be required haemopoietic stem cell transplant

- Senior MDT approach - input from:

- Haematology

- Rheumatology

- Cardiology

- Microbiology / Infectious Diseases

Specific Management

What are the goals of treatment in HLH?

- Suppression and control of hyperinflammation and elevated cytokine levels

- Elimination of activated and infected cells to remove ongoing stem stimulus for immune activation

Which drugs have been used in the management of HLH?

The classical HLH-94 protocol includes:

- Corticosteroids – usually dexamethasone in primary forms and methylprednisolone in secondary forms

- Etoposide – a chemotherapy agent with high specificity against T-cells

- Cyclosporin A

- Methotrexate

Other drugs that are commonly used include

- Anakinra (an interleukin-1 inhibitor)

- Immunoglobulin

- Alemtuzumab

- Tocilizumab

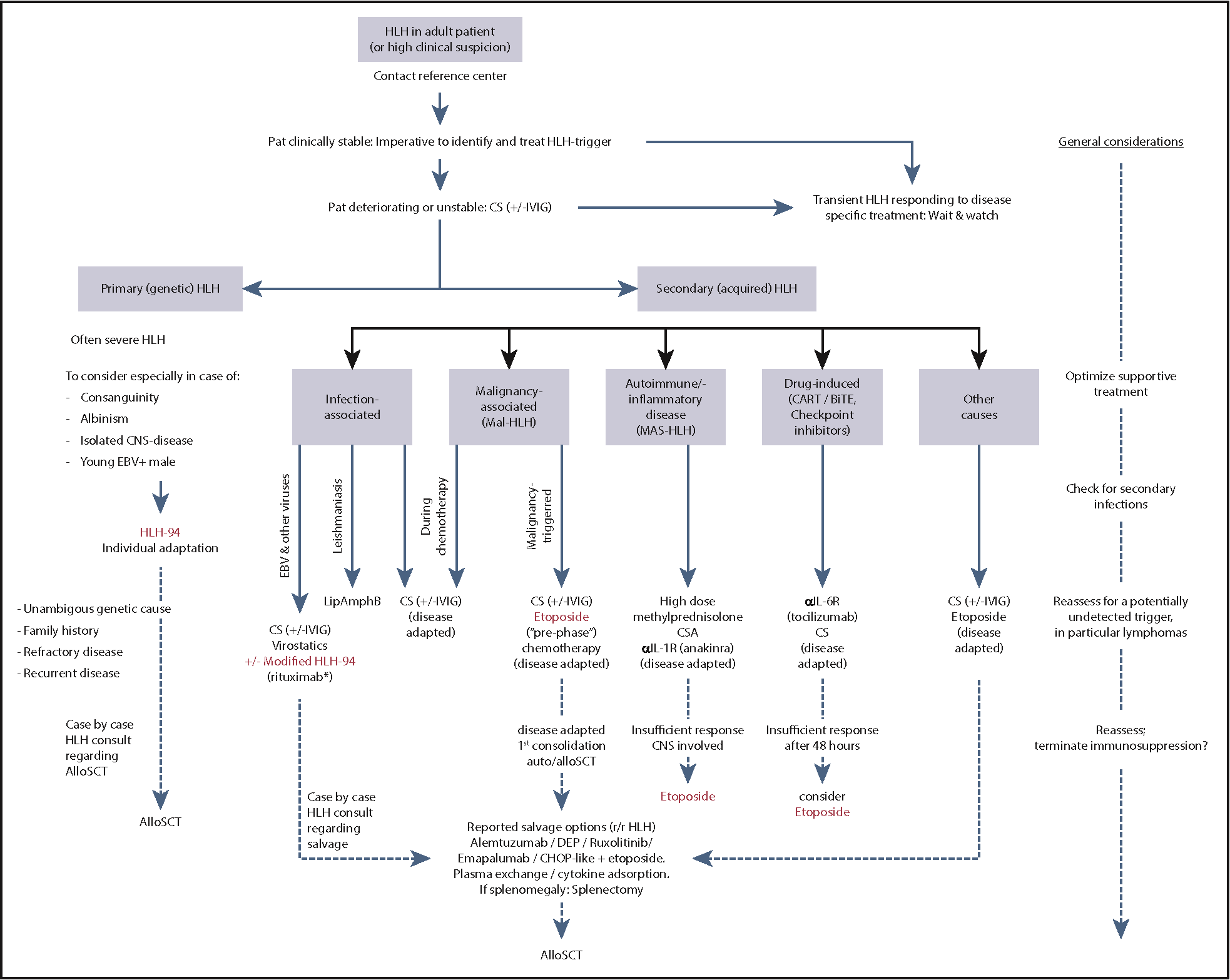

Which treatments should be selected for HLH?

- The heterogeneity of adult HLH prohibits a “1-size-fits-all protocol”

- Management is highly specialised and requires expert input

- A summary of commonly used management options is provided in the American Society of Haematology Guidance