RESOURCES

Review Articles

- Burton, BJA Ed (2004); Endocrine and Metabolic Response to Surgery

- Desborough, BJA (2000); The Stress Response to Trauma

- Finnerty, JPEN (2013); The Surgically Induced Stress Response

- Ivanovs, Pros Lat Acad Sci (2012); Stress Response to Surgery and Possible Ways of Its Correction

- Singh, Ind J Anaes Sci (2003); Stress Response and Anaesthesia

OBJECTIVES & QUESTIONS

Introduction

What is the stress response?

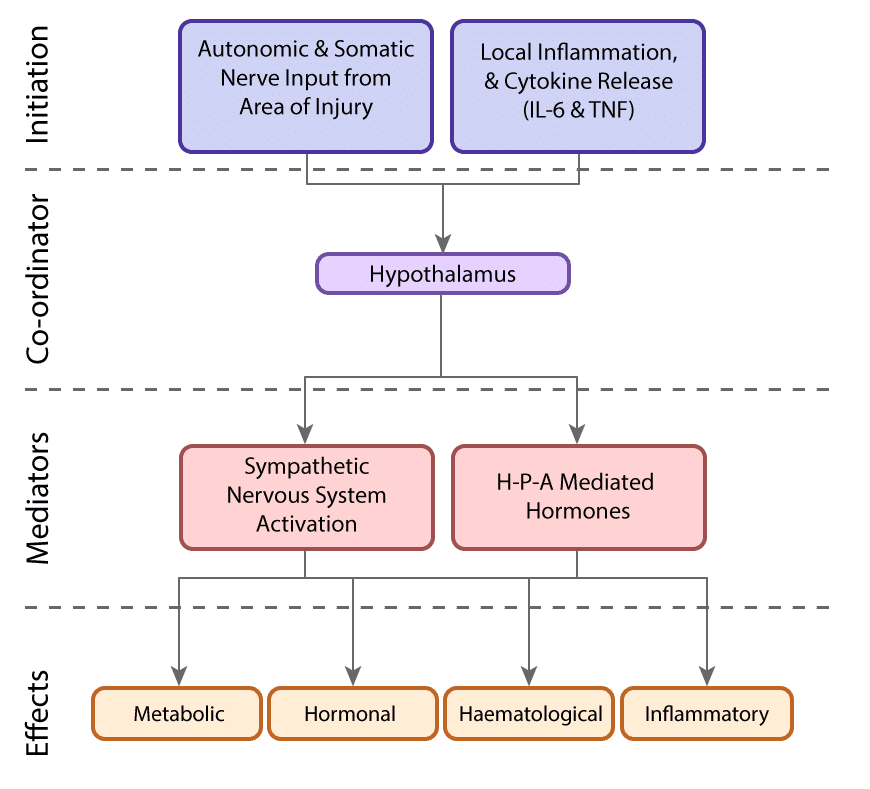

A group of complex neuroendocrine and metabolic changes that occur in response to trauma and surgery. The net effect is increased catabolism, substrate mobilisation and retention of salt and water

What is the purpose of the stress response?

- Likely developed as a useful evolutionary protective strategy to increase survival following injury:

- Mobilises fuel stores to survive without food

- Protective mechanisms to replenish circulating volume

- Response now felt to be detrimental in the context of modern surgery

- Physiological changes can adversely affect surgical outcomes

- Efforts are often made to obtund it where possible

What are the core components of the stress response?

What are the hormonal sequelae of the stress response?

- Growth Hormone (GH)

- Adrenocorticotrophic Hormone (ACTH)

- β-Endorphin

- Prolactin

- Anti-diuretic hormone (ADH)

- Catecholamines

- Cortisol

- Aldosterone

- Glucagon

- Renin

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Luteinizing hormone (LH)

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FH)

- Insulin

- Testosterone

- Oestrogen

- Tri-iodothyronine (T3)

What are the metabolic sequelae of the stress response?

What are the inflammatory sequelae of the stress response?

- Increased circulating cortisol has several effects:

- Suppresses the division of CD4+ T helper cells

- Decreases inflammation (prostaglandin synthesis and leucocyte migration)

- Overall effect is increased susceptibility to invading pathogens

Complications

What are the adverse consequences of the stress response?

What are the phases of the stress response?

Classically described as three distinct phases:

Timing: < 24 hours

Characterized by reconstruction of the body’s normal tissue perfusion and efforts to protect homeostasis. In this phase, there is a decrease in total body energy and urinary nitrogen excretion.

- Initial period of shock:

- ↓ cardiac output

- Hypotension may occur

- Lactic acid accumulates

- Acute inflammatory response occurs at the site of injury:

- Release of cytokineso

- Systemic vasodilatation follows

- The body tries to preserve volume:

- Hypercoagulable state to reduce bleeding

- Activation of RAA system

- ↑ ADH secretion

- ↑ sodium retention and ↓ urine output

- Neuro-Endocrine changes:

- ↑ Activation of sympathetic nervous system

- ↑ catecholamines

- ↑ glucagon and ↓ insulin

- Mildly ↑ glucose

- Period of ↓ metabolism:

- ↓ BMR

- ↓ temperature

- Substrate is mobilised but not utilised

Timing: 2-8 days

Characterized by catabolism and volume replacement to provide a compensating response to the initial trauma. Response is directed to the supply of energy and protein substrates to repair damaged tissues and protect critical organ functions. While necessary for survival in the short term, it can become damaging for the body when the response is severe or long-lasting.

- Period of hypermetabolism

- ↑ cardiac output

- ↑ O2 consumption

- Normal / high body temp

- Changes driven by:

- ↑ catecholamines

- ↑ Counterregulatory hormones

- ↑ cytokines

- Ongoing fluid & sodium retention to replenish volume:

- The third spacing of fluid occurs

- Widespread metabolic changes

- Carbohydrate metabolism

- ↑ Glycogenolysis

- ↑ Gluconeogenesis

- Insulin resistance of tissues•

- Hyperglycaemia

- Fat metabolism

- ↑ Lipolysis

- Free fatty acids used as energy substrate by tissues (except brain)

- Some conversion of free fatty acids to ketones in liver (used by brain)

- Glycerol converted to glucose in the liver

- Protein metabolism

- ↑ Skeletal muscle breakdown

- Amino acids converted to glucose in liver

- Shift toward production of acute-phase proteins

- Increased nitrogen excretion (negative nitrogen balance)

- Carbohydrate metabolism

Timing: 3-14 days

Characterized by the restoration of body weight, skeletal muscle mass and fat stores. Occurs following the period of catabolism, when the release of pro-inflammatory mediators has subsided, and is often associated with clinical improvement in patients such as increased appetite and mobility.

- Timing of transition depends on injury severity:

- 3–8 days after uncomplicated elective surgery

- Several weeks after severe trauma and sepsis

- Mediated by catabolic hormones:

- ↑ insulin

- ↑ growth hormone

- ↑ androgens

- Metabolic changes include:

- Gradual restoration of body protein and fat stores

- Transition to normal positive nitrogen balance

- Clinically coincides with

- ↑ diuresis

- ↑ appetite

- ↑ mobility

- Can last for several months after serious injury

How do the overall changes in the stress response compare with those seen in starvation?

What strategies can be used to minimise the stress response?

*Experimental strategies

- Reduction of Psychological Stress & Anxiety:

- Patient information

- Premedication with anxiolytics

- Optimal preoperative nutrition & hydration

- Carbohydrate loading

- Prevention of prolonged fasting

- Anaesthetic Technique:

- Appropriate doses of anaesthetic drugs & anaesthetic depth

- Regional & local anaesthetic blocks

- Opioid-sparing (multi-modal) analgesia

- Use of etomidate

- Surgical Technique:

- Minimally invasive surgical techniques

- Fluid & Temperature management:

- Avoidance of hypothermia

- Avoidance of excess fluid administration

- Catecholamine suppressing drugs:

- A2 agonists

- B blockers

- Hormonal modifiers:

- Glucocorticoids

- Anabolic agents (e.g. Growth hormone)

- Pain management:

- Minimisation of pain

- Opioid-sparing (multi-modal) analgesia

- Nutritional support:

- Early oral nutrition

- Adequate dietary protein

- Glycaemic control

- Immunonutrition

- Probiotics

- Environment & Interaction:

- Early mobilisation

- Exercise

- Avoidance of sleep disturbance