Time: 0 second

Question No. 2

Q: What are the clinical features that may suggest pulmonary embolism as a cause of a patients deterioration?

Answer No. 2

- Clinical features are non-specific and have been shown to be of limited value in confirming the diagnosis

- Features range from being relatively asymptomatic to significant cardiovascular compromise - they can be difficult to identify in the sedated, mechanically-ventilated patient

- Haemodynamic instability is a rare but important form of clinical presentation, as it indicates central or extensive PE with severely reduced haemodynamic reserve

- Common features include:

Symptoms

- Pleuritic chest pain

- Dyspnea

- Hemoptysis

Signs

- Acute onset of tachypnea

- Hypoxia or increased oxygen requirements

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Unexplained agitation

- Asymmetric leg swelling

- Weaning failure

- Persistent pyrexia without evident source of infection

- Cardiovascular and respiratory examination findings:

- Pleural friction rub

- Small volume arterial pulse

- Raised jugular venous pressure

- Gallop rhythm at the left sternal edge

- Accentuated second heart sound

Question No. 3

Q: How common is pulmonary embolism?

Question No. 4

Q: What is the mortality associated with pulmonary embolism?

Answer No. 4

- Mortality rates range in studies range from 6% - 15%

- In 2004 this equated to 370 000 deaths across Europe

- 34% died suddenly or within a few hours of the acute event

- 59% diagnosed after death

Only 7% who died early were correctly diagnosed with PE before death

Question No. 5

Q: What are the risk factors for VTE in the critically ill?

Answer No. 5

Can be considered according to Virchow’s triad:

Venous Stasis

- Prolonged bed rest

- Prolonged air travel (>8 hours)

- Fracture of lower limbs

- Hip or knee replacement

- Spinal cord replacement

- Varicose veins

Hypercoagulability

- Malignancy (particularly metastatic disease)

- Infection (specifically pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and HIV)

- Specific thrombotic conditions:

- Previous venous thrombosis

- Factor V Leiden mutation

- Protein C or S deficiency

- Hyperhomocysteinemia

- Antithrombin III deficiency

- Antiphospholipid antibodies

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

- High levels of factor VIII

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Pregnancy

- Drugs:

- Hormone replacement therapy

- Oral contraceptives

- Tamoxifen

- Chemotherapy

- Heart failure or respiratory failure

- Increasing age

- Obesity

Endothelial Injury

- Major surgical procedures

- Trauma

- Prior venous thrombosis

- Venous catheters

- Smoking

- Hypertension

Question No. 6

Q: How can the severity of PE be classified?

Answer No. 6

- Classification of PE severity has traditionally been based on haemodynamic stability:

Massive

- Cardiovascular compromise with a systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mmHg or a drop in systolic pressure of >40 mmHg

Sub-Massive

- No systemic hypotension but evidence of either RV dysfunction or myocardial necrosis

Mild / Non-Massive

- Asymptomatic or with mild symptoms and no evidence of RV dysfunction or cardiovascular compromise

- Newer classifications of severity are based upon early mortality risk (in-hospital or 30-days) using clinical, imaging, and laboratory indicators:

Early Mortality Risk

Early Mortality Risk

Risk Parameters & Scores

Risk Parameters & Scores

Risk Parameters & Scores

Risk Parameters & Scores

Early Mortality Risk

Early Mortality Risk

Shock or hypotension

PESI class III-V

Signs or RV Dysfunction on Imaging

Cardiac Laboratory Biomarkers

High

High

+

(+)

+

(+)

Intermediate

High

-

+

Both positive

Both positive

Intermediate

Low

-

+

Either one (or none) positive

Either one (or none) positive

Low

Low

-

-

-

Assessment optional but negative if assessed

Question No. 7

Q: How is haemodynamic instability defined in the setting of high-risk pulmonary embolism?

Answer No. 7

Cardiac arrest

- Need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Obstructive shock

- Systolic BP <90 mmHg or vasopressors required to achieve a BP ≥90 mmHg despite adequate filling status

and - End-organ hypoperfusion (altered mental status; cold, clammy skin; oliguria/anuria; increased serum lactate)

Persistent hypotension

- Systolic BP <90 mmHg or systolic BP drop ≥40 mmHg, lasting longer than 15 min and not caused by new-onset arrhythmia, hypovolaemia, or sepsis

Question No. 9

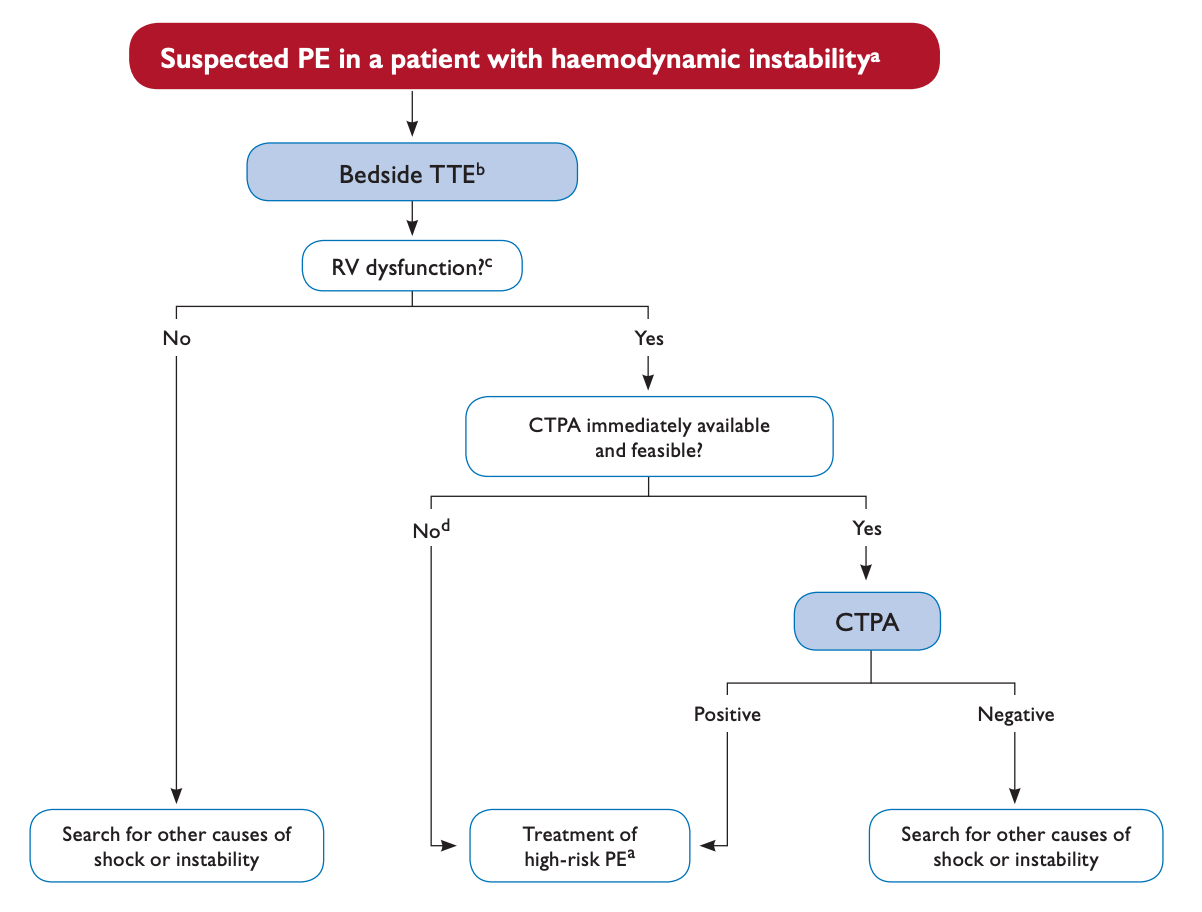

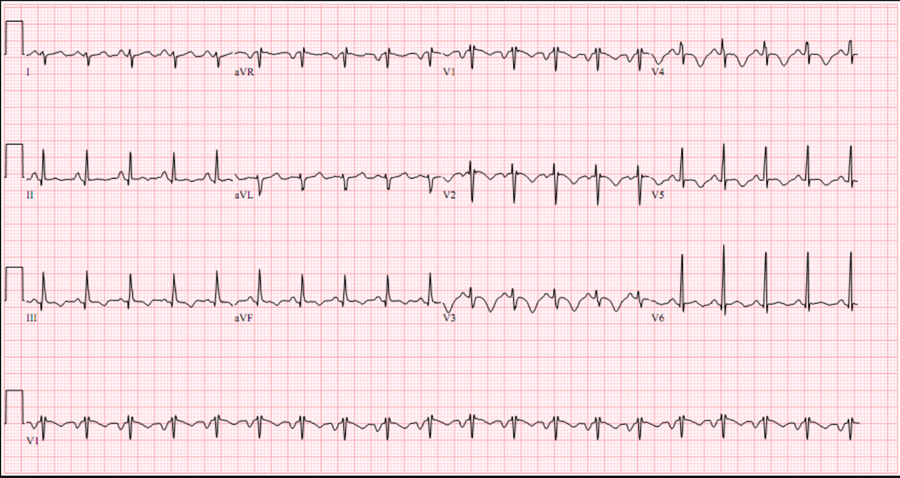

Q: What are the electrocardiographic (ECG) findings seen in PE?

Answer No. 9

- ECG findings are also variable and neither sensitive or specific

- A normal ECG is seen in up to 18% of cases

- Abnormalities seen include:

- Sinus tachycardia (most common - 44%)

- Atrial arrhythmias (most frequently atrial fibrillation)

- Classic S1Q3T3 (10%)

- Deep S-wave in lead I, Q-wave in III and an inverted T-wave in III

- Complete or incomplete right bundle branch block (15%): rSR’ in V1

- Associated with increased mortality

- Acute right ventricular strain (34%)

- T-wave inversion in the right precordial leads (V1-4) and the inferior leads (II, III, aVF)

Associated with high pulmonary artery pressures

- T-wave inversion in the right precordial leads (V1-4) and the inferior leads (II, III, aVF)

- Right axis deviation (15%):

- May be extreme deviation - between 0 and -90°

- Non-specific ST-segment and T-wave changes:

- ST-elevation and depression

- T-wave inversion

An ECG in pulmonary embolism demonstrates:

- S1Q3T3 pattern - an S wave in lead I, Q wave and an inverted T wave in lead III

- Sinus tachycardia

An ECG in pulmonary embolism demonstrates:

- Incomplete or complete RBBB (rSR’ in V1)

- T wave inversion in V1-V3 - mimics anterior ischemia

- Sinus tachycardia

An ECG in pulmonary embolism demonstrates:

- Right axis deviation

- Right bundle branch block (rSR’ in V1)

- Deep T wave inversion in V1-V3

- Sinus tachycardia

Question No. 11

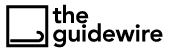

Q: Why do pulmonary emboli cause haemodynamic instability?

Answer No. 11

- PE can lead to right ventricular (RV) failure due to acute pressure overload:

- Pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) increases in the presence of obstruction

- Becomes evident if >30-50% of the total cross-sectional occluded by thromboemboli

- Obstruction due to:

- Mechanical obstruction from clot burden

- Vasoconstriction, mediated by the release of thromboxane A2 and serotonin

- Results in increased RV afterload and subsequent dilatation:

- Initial compensation occurs via Frank Starling mechanism with increased myocyte stretch

- Neurohumoral activation leads to inotropic and chronotropic stimulation.

- RV adaptation is limited and is unable to generate a mean PAP >40 mmHg

- Ventricle non-preconditioned and thin-walled

- Enters cycle of progressive RV failure with imbalanced oxygen supply / demand and decreased contractility

- Progressive impact on left ventricle (LV) and systemic circulation:

- Bowing of intraventricular septum impairs LV filling

- Further exacerbated by development of right bundle branch block

- Leads to reduced cardiac output and systemic hypotension

- Exacerbates impaired coronary driving pressure to the overloaded RV and further imbalances myocardial oxygen supply and demand

- May be a secondary inflammatory response due to massive neurohumoral activation

Question No. 12

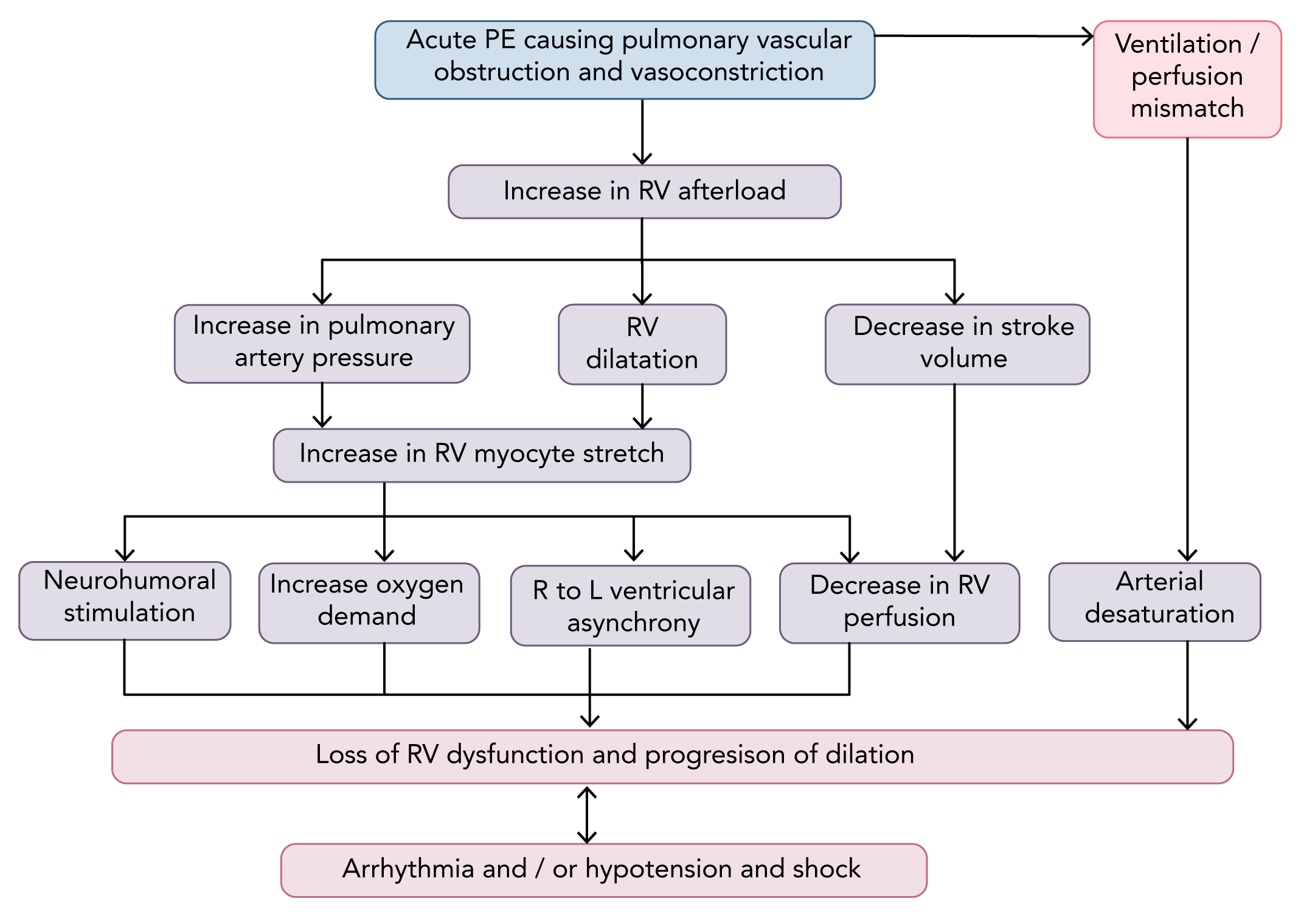

Q: How would your diagnostic strategy change now the patient is demonstrating haemodynamic instability?

Answer No. 12

Question No. 13

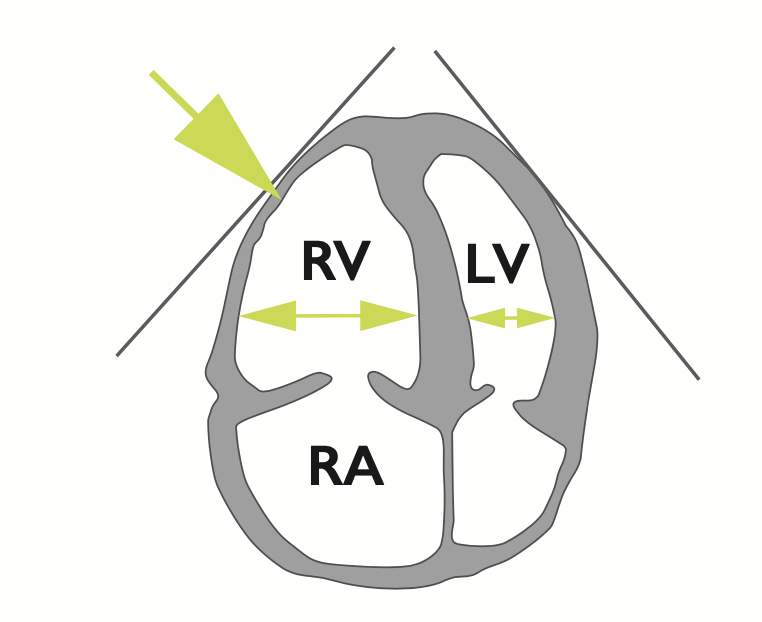

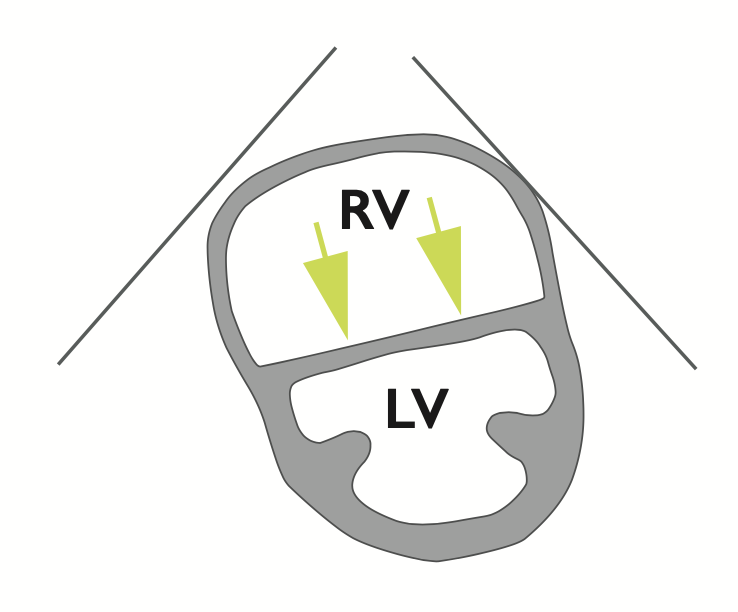

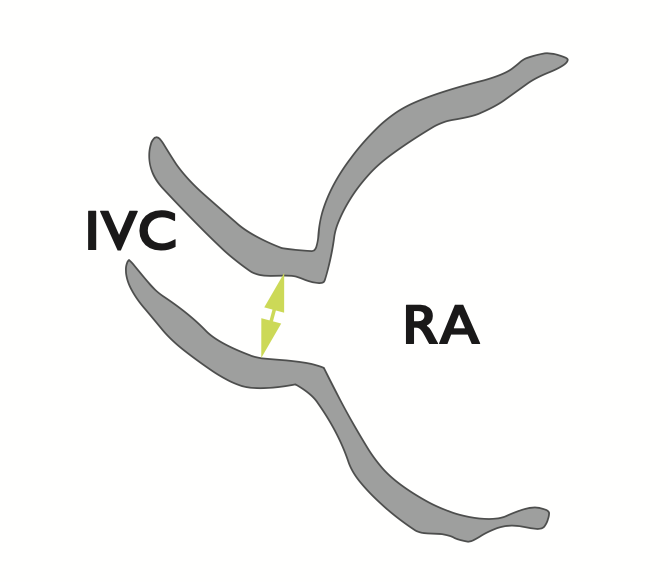

Q: What are the echocardiographic findings seen in PE?

Answer No. 13

- Dilatation of the right ventricle

- Impaired right ventricular function

- Flattened intraventricular septum

- Distended inferior vena cava with diminished inspiratory collapsibility

- Tricuspid regurgitation

- Mobile thrombus in the right heart

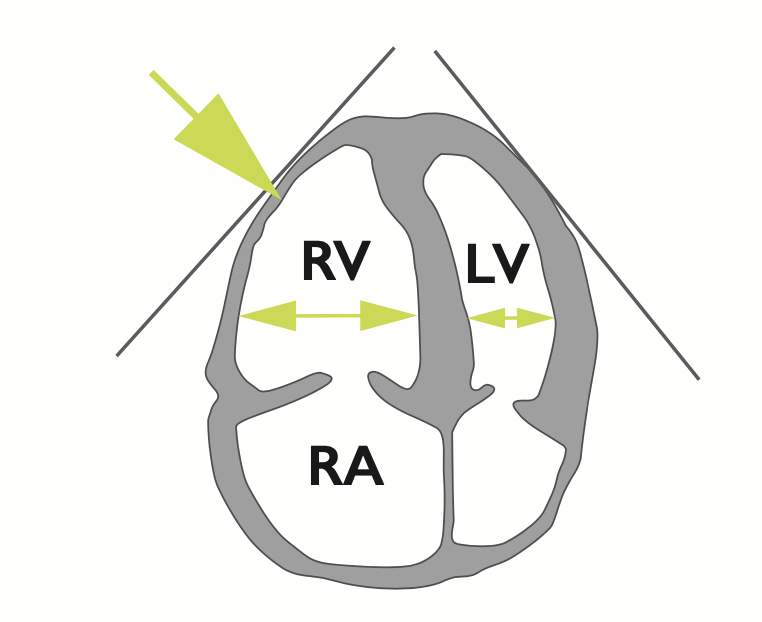

Dilatation of the right ventricle

- Basal RV/LV > 1.0

- RV >4cm at the base in the 40 chamber view

Impaired right ventricular function

- Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) <16 mm

- May be evident on visual evaluation

McConnel's sign

- Normokinesia and/or hypokinesia of the apical segment of the RV free wall despite hypokinesia and/or akinesia of the remaining parts of the RV free wall

Flattened intraventricular septum

Distended inferior vena cava with diminished inspiratory collapsibility

Tricuspid regurgitation

- Velocity greater than 2.7 m/sec by colour doppler flow imaging

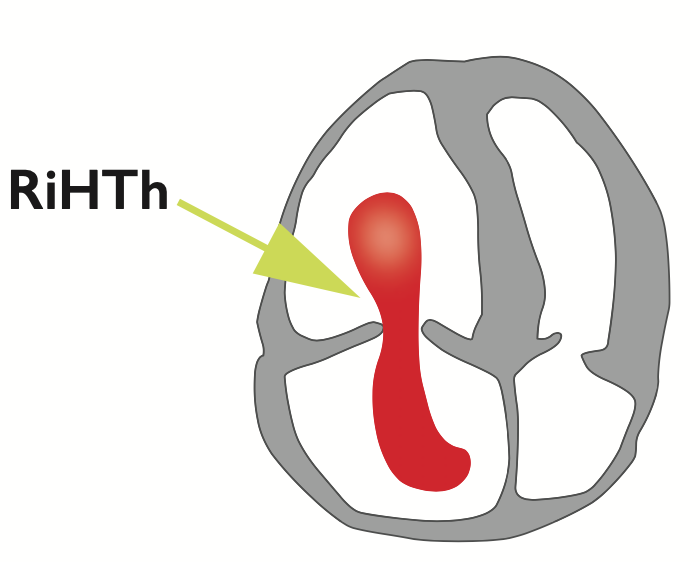

Mobile thrombus in the right heart

Question No. 14

Q: What are the indications for thrombolysis in PE?

Answer No. 14

- High-risk (massive) PE

- Selected cases of intermediate-risk (sub-massive) PE:

- Currently not routinely recommended by ESC guidance

- Some evidence it improves long term outcomes

Question No. 15

Q: What is the role for thrombolysis in sub-massive PE?

Answer No. 15

- Some argue in favour of thrombolysis given improved longer-term outcomes:

- Reduced burden of chronic RV failure or thrombus-related pulmonary hypertension

- Others argue against thrombolysis given:

- Relatively low mortality rates even with standard treatment (heparin)

- Lack of proven mortality benefit (PEITHO trial used composite endpoint of mortality and haemodynamic instability)

- Known potential for serious morbidity/ mortality with thrombolytics (mainly due to intracranial bleeding)

- Increased cost

- European Society of Cardiology guidelines do not currently recommend thrombolysis for intermediate-risk (sub-massive) pulmonary embolism

Question No. 16

Q: What is the evidence for thrombolysis in intermediate-risk (sub-massive) PE?

Answer No. 16

Study

Intervention

Population

Conclusion

- Thrombolysis (tenecteplase 30-50mg & heparin) vs. no thrombolysis (placebo & heparin) in patients with intermediate-risk/sub-massive pulmonary embolism

- 1006 patients across 76 sites in 13 countries

- PE confirmed by V/Q, CT or pulmonary angiogram with RV dysfunction confirmed by echo or CT and raised troponin

- Primary outcome: Death or haemodynamic decompensation (composite endpoint) within 7 days significantly lower in thrombolysis group than placebo group (2.6%5.6%)

- Secondary outcomes:

- No significant difference in mortality (1.2% vs. 1.8%)

- Both major extracranial bleeding (6.3% vs. 1.2%) and haemorrhagic stroke (2% vs 0.2%) significantly higher in thrombolysis group

- Thrombolysis (tenecteplase & heparin) vs. no thrombolysis (heparin alone) in patients with intermediate-risk/sub-massive pulmonary embolism

- 83 patients across 8 sites in the USA

- PE confirmed by V/Q, CT or pulmonary angiogram with RV dysfunction confirmed by echo, troponin or BNP

- Composite primary outcome of death, intubation and major bleeding at 5 days or recurrent PE or impaired functional capacity at 90 days

- Significantly reduced adverse outcomes in thrombolysis group (15% vs. 37% had at least 1 adverse outcome)

- Thrombolysis with half standard dose thrombolysis (tPa & enoxaparin) vs. anticoagulation alone in 'moderate PE'

- 121 patients in single centre in the USA

- 'Moderate PE' defined as haemodynamically stable PE with >70% involvement of thrombus in ≥2 lobar or left or right main pulmonary arteries

- Primary outcome of development of pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≥ 40mmHg) significantly lower in thrombolysis group than control group(16% vs. 57%)

Question No. 17

Q: What surgical and catheter reperfusion therapies are available and what are their roles?

Answer No. 17

- Should be considered:

- Where there are absolute contraindications to thrombolysis

- Where thrombolytic therapy has failed and the patient is critically ill

- Options include:

Percutaneous Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis / Embolectomy

- Involves insertion of a catheter into the pulmonary arteries via the femoral route

- Different approaches involve one or a combination of:

- Mechanical fragmentation

- Ultrasound fragmentation

- Thrombus aspiration

- In situ reduced-dose thrombolysis

- Overall procedural success rates in small studies have reached 87%

Surgical Embolectomy

- Carried out with cardiopulmonary bypass, with aortic cross-clamping and cardioplegic cardiac arrest

- Involves incision of the two main pulmonary arteries with the removal or suction of fresh clots

- Has favourable outcomes in small studies:

- Similar 30-day mortality to thrombolytic therapy

- Lower risk of stroke or re-intervention

Question No. 18

Q: What are the options for anticoagulation for a patient presenting with pulmonary embolism?

Answer No. 18

Acute Management

Parenteral, weight-adjusted anticoagulation should be used:

- Low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) SC

- Fondaparinux SC

- Unfractionated heparin (UFH) IV

- Generally second line due to higher bleeding risk and HIT risk

- Preferred agent in the setting of:

- Overt haemodynamic instability or imminent haemodynamic decompensation in whom primary reperfusion treatment will be necessary (short half life and easy reversal)

- Increased risk of bleeding

- Serious renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min)

Longer-Term Management

Started when the patient's condition is stable and no invasive procedures are planned

- Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant (NOAC)

- Warfarin international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 to 3.0:

Question No. 19

Q: When should anticoagulation be commenced?

Answer No. 19

- Anticoagulation should be initiated without delay, while diagnostic workup in progress, in patients with:

- Suspected PE with haemodynamic instability

- Suspected PE without haemodynamic instability with a high or intermediate clinical probability

Question No. 20

Q: When should intubation be considered in pulmonary embolism?

Answer No. 20

- Patients at high risk of deterioration during induction of anaesthesia, intubation, and positive-pressure ventilation:

- Effect of drugs on hypotensive patient

- Positive intrathoracic pressure reduces venous return and exacerbates RV dysfunction

- Intubation should be performed only if the patient is unable to tolerate or cope with non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen therapy

Question No. 21

Q: How should right ventricular failure be managed in pulmonary embolism?

Answer No. 21

Fluid Therapy

- Cautious fluid therapy may improve haemodynamic status:

- Small fluid boluses (500ml) have been shown to improve cardiac output

- Aggressive volume expansion should be avoided:

- Potential to over distend the RV and lead to reduced systemic cardiac output

- Not shown to be of benefit in studies and may be harmful

- If signs of elevated CVP, further volume loading should be withheld

Vasopressors & Inotropes

- Noradrenaline considered as first line therapy:

- Increases RV inotropy and systemic blood pressure

- Restores coronary perfusion gradient and improves ventricular interactions

- Dobutamine may be considered useful for patients with PE, a low cardiac index and normal:

- Potential to aggravate ventilation/perfusion mismatch

- Can worsen circulatory failure given vasodilatory effect

Pulmonary Vasodilators

- May be useful in in patients with PE and pulmonary hypertension, though anecdotal evidence only

- Options include inhaled nitric oxide and aerosolised prostacyclin

Mechanical Circulatory Support

- May be useful in the setting of circulatory collapse or cardiac arrest:

- VA-ECMO most frequently used:

- Associated with a high incidence of complications, even when used for short periods

- Effectiveness depends upon centre experience and patient selection