Time: 0 second

Question No. 2

Q: What is a subarachnoid haemorrhage?

Answer No. 2

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is the presence of blood in the subarachnoid space, between the pia and arachnoid dural membranes

- Approximately 5% of all cerebrovascular events in the United Kingdom are the result of a SAH

- Symptoms and signs include the classical 'thunderclap' headache, focal neurological signs, reduced GCS, and signs of meningism

- It is associated with a high disability rate and mortality

Question No. 3

Q: What are the symptoms & signs of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 3

Symptoms

- Sudden onset headache (70-80%):

- 'Worst ever' or 'thunderclap' in nature

- Occipital location is classic

- Sentinel headache in 40%

- Nausea and vomiting (77%)

Signs

- Fluctuating / loss of consciousness (53%)

- Signs of meningism (35%):

- Neck stiffness

- Photophobia

- Kernig’s sign

- Seizures (10-40%)

- Focal neurological signs

- Ophthalmic signs:

- Sub-hyaloid retinal haemorrhage

- Papilloedema

- Pyrexia

Question No. 4

Q: How common is subarachnoid haemorrhage and who is affected?

Answer No. 4

- Accounts for 5% of strokes in the UK

- Incidence of 9 per 100,000 adults per year

- More common in:

- Women

- Older age with a peak around 50 years

- Aneurysms account for about 85% of spontaneous SAH

Question No. 5

Q: What is the prognosis for people with subarachnoid haemorrhage?

Answer No. 5

- Mortality rates currently 35-50% (incidence varies highly in studies)

- Of those that die:

- ~15% die prior to reaching hospital

- 60% die within first 24 hours

- 19% die within 1 week

- 6% die within 3 weeks

- 1% die later than 3 weeks

- High long term morbidity for survivors:

- ~ 20-30% will be dependent on carers

- Up to half have cognitive impairment sufficient to affect quality-of-life

- Prognosis worsens with increasing severity grade (Glasgow outcome scale 1-3 or modified Rankin scale 4-6):

WFNS (World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies) Grade

Proportion with Bad Outcome

I

14.8%

II

29.4%

III

52.6%

IV

58.3%

V

92.7%

Question No. 6

Q: What are the causes of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 6

Individual Factors

- Female gender

- Age (peak incidence 40-60)

- Previous aneurysm or SAH

- Family history

- Smoking

- OCP

- Alcohol abuse

Parenchymal

- Hypertension:

- Atherosclerotic disease

- Cocaine or sympathomimetic use

- Connective tissue disorders:

- Marfan's syndrome

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Vasculitides

- Alpha 1 anti-trypsin deficiency

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Neurofibromatosis

Question No. 7

Q: What are the risk factors for developing a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 7

Individual Factors

- Female gender

- Age (peak incidence 40-60)

- Previous aneurysm or SAH

- Family history

- Smoking

- OCP

- Alcohol abuse

Parenchymal

- Hypertension:

- Atherosclerotic disease

- Cocaine or sympathomimetic use

- Connective tissue disorders:

- Marfan's syndrome

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Vasculitides

- Alpha 1 anti-trypsin deficiency

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Neurofibromatosis

Question No. 8

Q: What are the pathophysiological processes that lead to brain injury in subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 8

- When an aneurysm ruptures:

- Blood pushes into the subarachnoid space at arterial pressure

- Intracranial pressure equalizes across the rupture site and stops the bleeding

- Thrombus formation at the bleeding site.

- Physical damage due to bleeding and mass effect

- Early brain injury occurs due to:

- Raised intracranial pressure

- Decreased cerebral blood flow

- Complex pathological process ensues characterised by:

- Microthrombosis, oedema, blood-brain-barrier disruption and inflammation

- Results in apoptosis, necrosis and cell death

- Leads to global cerebral ischaemia and infarction

- Sympathetic activation produces systemic manifestations

Question No. 10

Q: Describe your initial management of patient with suspected SAH?

Answer No. 10

Resuscitation & Supportive Care

- Consider need for intubation:

- Intubation if not maintaining airway

- May require semi-elective intubation if not protecting adequately or for neuroprotective measures

- Tape tube in position

- Manage hypertension / hypotension

- Until aneurysm secured target systolic blood pressure <180mmHg-160mmHg (ESO/AHA)

- If required use a titratable IV antihypertensive and invasive arterial monitoring

- Maintain MAP >90mmHg (ESO)

- Manage arrhythmias

- Manage seizures with benzodiazepines, phenytoin and levetiracetam

- Instigate appropriate neuroprotective measures:

- Maintain CO2 4.5-6.0 kPa, pO2 >10

- Sit up, avoid neck lines

- Analgesics, laxatives, antiemetics to reduce ICP

- Maintain glucose 6-10mmol and temperature <37.5

- Careful management of fluids:

- Urinary catheter and fluid balance monitoring for all patients

- Aim for euvolaemia

- Reverse any coagulopathy

- DVT prophylaxis:

- Mechanical methods until aneurysm secured

- LMWH >12 after surgical clipping

Question No. 11

Q: What would make you consider intubation in a patient with a suspected subarachnoid haemorrhage?

Answer No. 11

- GCS <8

- Drop in GCS >2 points

- Optimization of ventilation

- Seizures

- To facilitate transfer to neurosurgical centre

- Uncontrolled hypertension in the presence of an unsecured aneurysm

Question No. 12

Q: How do you work up the patient with suspected subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 12

To Determine Diagnosis

- CT head:

- Detects the presence of subarachnoid blood

- Highly sensitive on day 1 (>95%) but reduced thereafter (50% on day 5)

- MRI an alternative though not readily available at most centres

- LP:

- Detects presence of xanthochromia

- Should be performed >12 hours after symptom onset if CT non-diagnostic

To Assess Severity / Prognosis

- Graded using clinical severity scale:

- World Federation of Neurosurgeons (WFNS)

- Prognosis on Admission of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (PAASH)

- Hunt & Hess

To Determine Aetiology

- CTA: assesses vascular anatomy

- Digital subtraction cerebral angiography (DSA):

- Remains the gold standard

- Allows intervention

- MRI: mostly used for detection of AVM

- Screen for vasculitis and amyloidosis

To Assess for Complications

- To assess for cardiac dysfunction:

- ECG - peaked T waves, ST depression, prolonged QT, arrhythmias

- Echo - neurogenic cardiomyopathy, regional wall motion abnormalities

- Troponin

- Pro-BNP

- To assess for metabolic dysfunction:

- Plasma and urinary sodium / osmolality

- Urine output monitoring

- To assess for respiratory dysfunction:

- CXR - pulmonary oedema

- ABG

Question No. 14

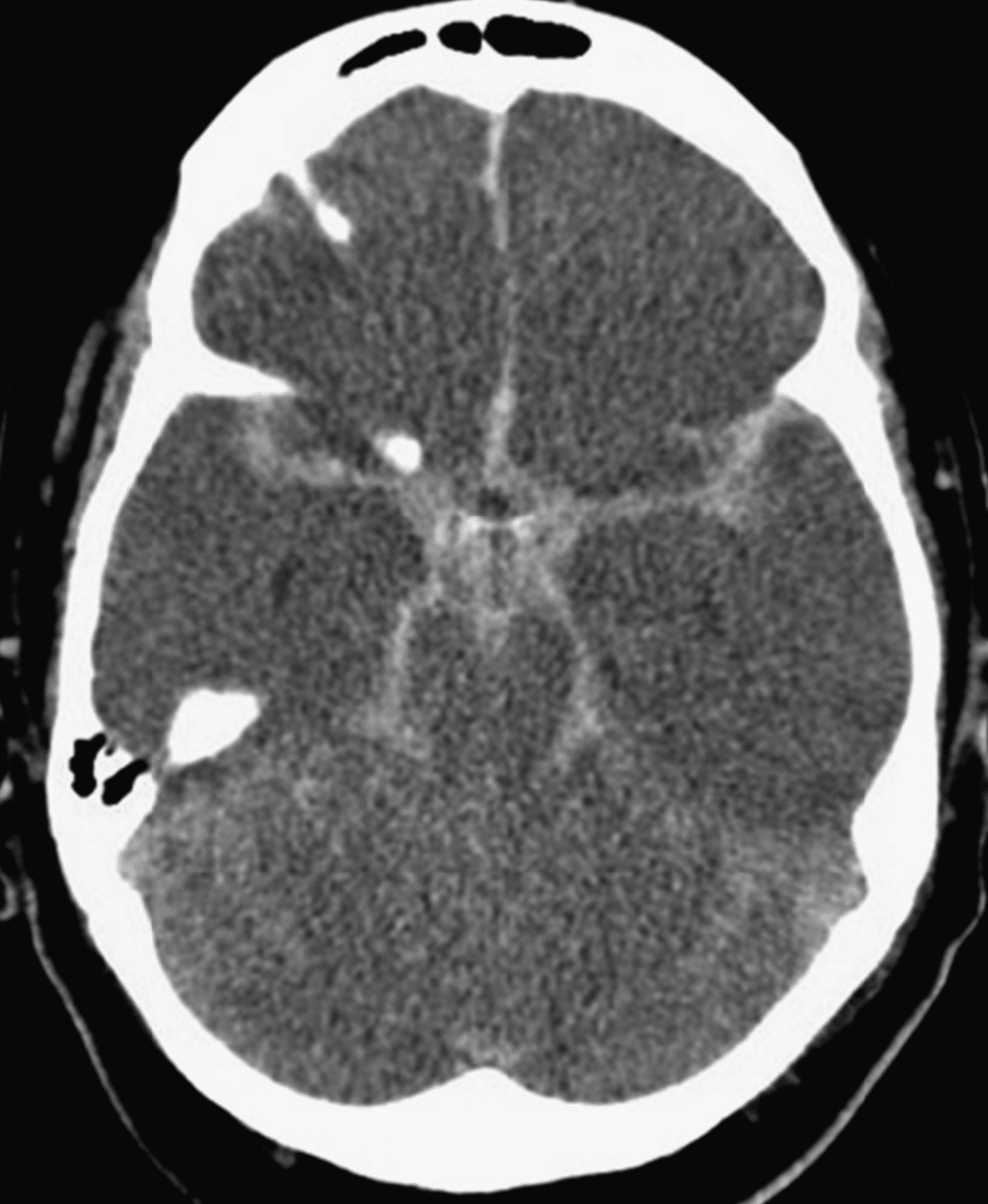

Q: Describe the findings of the CT?

Answer No. 14

- There is hyperdense blood within the basal cisterns, Sylvian and interhemispheric fissures - classical "star sign" distribution with blood distributed around 'circle of Willi's and along basal vessels

- There is loss of grey-white matter differentiation

Question No. 15

Q: Do you know of any grading systems that can be used in subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 15

Clinical

Clinical

Clinical

Radiological

WFNS (World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies)

Hunt & Hess

Prognosis on Admission of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (PAASH)

Fisher

Grade 1

GCS score of 15 without focal deficit

Asymptomatic or minimal headache and slight neck stiffness

GCS 15

No SAH detected

Grade 2

GCS score of 13 or 14 without focal deficit

Moderate to severe headache and neck stiffness

No neurologic deficit except cranial nerve palsy

No neurologic deficit except cranial nerve palsy

GCS 11–14

Diffuse or vertical layer of subarachnoid blood <1mm thick

Grade 3

GCS score of 13 or 14 with focal deficit

Lethargy or confusion

Mild neurological deficit

Mild neurological deficit

GCS 8–10

Localized clot and/or vertical layer within the subarachnoid space >1mm thick

Grade 4

GCS score of 7-12

Stuporous

More severe neurological defecit

Possibly early decerebrate rigidity and vegetative disturbances

More severe neurological defecit

Possibly early decerebrate rigidity and vegetative disturbances

GCS 4–7

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) with diffuse or no SAH

Grade 5

GCS score of 3-6

Deep coma

Decerebrate rigidity and posturing

Decerebrate rigidity and posturing

GCS 3

Question No. 16

Q: What are the complications that can occur after subarachnoid haemorrhage?

Answer No. 16

Neurological

- Vasospasm and cerebral ischaemia

- Hydrocephalus

- Re-bleeding

- Seizures

- Cerebral oedema and raised ICP

- Focal neurology due to haemorrhage

Systemic

Metabolic

- Fever

- Hyperglycemia

- Disorders of sodium balance (50-60%):

- Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

- Cerebral salt wasting syndrome

- Diabetes insipidus

- Hypokalaemia

- Hypomagnesaemia

Respiratory

- Neurogenic / cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

- Pneumonia

- ARDS

- Atelectasis

Cardiovascular

- Neurogenic stunned myocardium syndrome (15%) - catecholamine induced, similar to Takutosubo's:

- LV dysfunction (systolic and diastolic)

- Regional wall motion abnormalities

- Cardiogenic shock

- ECG changes and troponin rise

- Arrhythmias

- Venous thromboembolism

Question No. 19

Q: How can a ruptured aneurysm be secured following subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 19

Coiling

- Endovascular treatment which involves navigating a catheter to the aneurysm site under fluoroscopic guidance

- A microcatheter is then advanced into the aneurysm sac and metal coils are deposited

- Coils arrest blood flow and induces thrombus formation which occludes aneurysm

- The coils are kept within the aneurysm sac an out of the vessel lumen by either a stent (stent-assisted coiling) or a balloon (balloon-assisted coiling)

Clipping

- Requires a craniotomy and exploration of the subarachnoid spaces around the cerebral arteries

- Once the aneurysm is exposed, a single or multiple titanium clips are placed across the neck of the aneurysm

- Results in mechanical occlusion the sac at its neck while preserving blood flow through the vessel lumen

Stenting

- Endovascular insertion of stents may be utilised in certain situations

- Flow-diverting stents are a new generation of stents designed to occlude the aneurysm by isolating the sac from the circulation - useful in fusiform and wide neck aneurysms

- Simple stenting is often used to treat dissecting aneurysms of the cerebral vessels

Trapping

- Used for giant aneurysms (>25mm diameter) where other methods have failed

- The aneurysm is trapped by two clips applied to the vessel either side

- A bypass graft is then used to provide blood flow to the distal vessels

Question No. 20

Q: When should an aneurysm be secured following subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 20

- Securing of the aneurysm should be performed as early as is feasible in the majority of patients to reduce rebleeding

- The aim should be to intervene within 72 hours of first symptoms

Question No. 21

Q: How is it decided whether an aneurysm should be managed by coiling or cilpping?

Answer No. 21

- Should be an MDT decision made by experienced surgeons and radiologists

- Decision based on:

- Characteristics of the patient:

- Surgical approach favoured in younger age and in presence of space occupying ICH

- Radiological approach favoured in older age, poor grade SAH and in presence of significant co-morbidities

- Characteristics of the aneurysm:

- Surgical approach favoured with:

- Middle cerebral artery aneurysm

- Wide aneurysm neck

- Arterial branches exiting directly out of the aneurysmal sac

- Radiological approach favoured with:

- Posterior location

- Small aneurysm neck

- Technical skills and availability

- Surgical approach favoured with:

- Characteristics of the patient:

- Coiling is the preferred treatment where it is judged that the aneurysm is amenable to either coiling or clipping

Question No. 22

Q: Is there any evidence to support the use of coiling over clipping in the management of a ruptured aneurysm following subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)?

Answer No. 22

- The largest trial comparing surgical and endovascular management of ruptured aneurysms is the ISAT trial:

Intervention

Population

Conclusion

- Endovascular coiling vs. surgical clipping for acute ruptured intracranial aneurysm

- 2143 with ruptured intracranial aneurysms

- Risk of death or dependence at 1 year (primary outcome) was significantly less common in those that received endovascular coiling (23.5% vs 30.9%, ARR 6-9%, 95%CI 3.6 - 11.2%)

- Longer term follow-up from this trial has raised concerns about delayed re-bleeding and higher need for retreatment